A History of Spanish Bullfighting

Share

The exact origins of bullfighting are debated, but one thing is certain: Spain's fascination with bulls is not a recent phenomenon. In fact, bulls have played an important role in the culture of the Iberian peninsula since before recorded history, with Paleolithic rock art from over 30,000 years ago depicting aurochs, the wild ancestors of modern bulls.

Cave paintings of aurochs found in Spain's Altamira Caves

For thousands of years, aurochs were hunted, eaten, and tamed in the region, and they were revered as symbols of strength and male fertility - in part because of their large, visible testicles. Conquering a bull in a hunt was thus seen as evidence of a man's own strength and masculinity, just as it remains today. Bulls also played a central role in pagan religions practiced by Celtiberian tribespeople in the Iberian peninsula in the last few centuries BCE, with religious worship involving bull sacrifices.

Beyond the Iberian peninsula, civilizations such as ancient Egyptians, Minoans, Sumerians, and Greeks also conducted rituals involving bull worship and sacrifice, which likely influenced the evolution of bullfights in Spain. For example, in ancient Egypt, the cult of Apis, which originated around 2775 BCE, worshipped a bull god who is widely believed to be the first god of Egyptian mythology. By 1200 BCE, bulls bred for ceremonies honoring Apis were pitted against each other in a bloodless fight; this early form of bullfighting is still practiced in many rural communities around the world, such as in parts of Kenya and the United Arab Emirates.

Furthermore, bull-dances involving acrobatic leaps were performed in ceremonies venerating the Minoan mother goddess, who was often depicted holding or accompanied by bulls. The Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 2150-1400 BCE), an epic poem from Mesopotamia, describes the hero Gilgamesh dancing around, fighting, and eventually killing the "Bull of Heaven." In ancient Greece, worship of the god Dionysus, who was sometimes depicted riding a bull, often “dissolved into cult techniques that sought to harness the bull’s sexual potency for human purposes” through ritualistic bull slaughter (Timothy Mitchell. Blood Sport: A Social History of Spanish Bullfighting, p. 40).

Fresco of a Minoan Bull-Leaper at the Minoan palace of Knossos in Crete (1450BCE)

Bulls were also significant in ancient Rome, which directly influenced the tradition of bullfighting in Spain through the expansion of the Roman empire. For example, gladiatorial events included an early form of bullfights, in which gladiators were sent to face bulls with only a sword. Also, between the 1st and 4th centuries CE, many Romans practiced a secret religion with Persian origins, known as the "Cult of Mithras," which held that the known world was created when the god Mithras slayed the "Cosmic Bull."

Although much remains unknown about the Cult of Mithras, scholars believe that initiation into this male-only cult required members to kill a bull to prove their worthiness. This religion flourished among the Roman imperial army, which spread these traditions and beliefs to the Iberian peninsula, and they constructed several shrines called Mithraeums to honor the god. In one particularly graphic depiction of a Mithraeum from the 4th-century CE, a priest wearing a silk toga and a golden crown stands in a pit underneath a platform on which a bull is slaughtered. The bull's blood rains into the pit and covers the priest, who opens his mouth to drink it as it pours over his face.

3rd century CE Fresco in Marino, Italy of Mithras killing the Cosmic Bull

As Christianity took hold in the Roman empire towards the end of the 4th century CE, efforts were made to break up the pagan Cult of Mithras and ban its traditions. Mithraic temples were turned into churches, and Romans issued decrees that banned bullfighting across the empire. However, this tradition still took place in secret, and by the 5th century CE, Visigoth governance in Hispania accepted and even encouraged bullfighting. A few centuries later, in 711 CE, Moors from northern Africa invaded and conquered Spain (then called Al-Andalus). The Moors fought bulls from horseback as a pastime, and they turned bullfighting into a more rule-based, ritualized sport.

By the 8th century CE, bullfights fought on horseback became a beloved public spectacle. Bullfights took place in amphitheaters, fields outside of small towns, and in public squares, or plazas - which is why today's bullrings are called Plazas de Toros. In the following centuries, bullfights continued to grow in popularity across Spain as a sport for nobles, and by the 11th century CE, Rodriguez Díaz de Vivar - nicknamed El Cid Campeador - was recognized as the first Castilian to fight a bull from horseback in an arena. From this point on, bullfights were an inseparable part of Spanish culture.

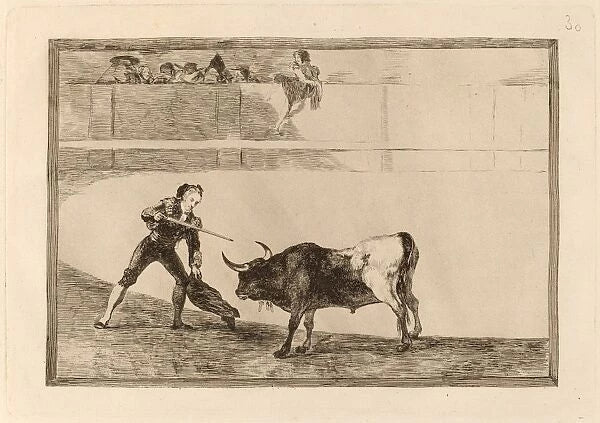

Plate 30 from "La Tauromaquia": Pedro Romero Killing the Halted Bull by Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1816)

In the following centuries, the sport of bullfighting only continued to grow in Spain; however, in 1567 CE, Pope Pius V attempted to ban the sport, stating that it was "more the character of demons than of men." In his ruling, Pope Pius V took a hard stance on the topic by vowing to excommunicate Christian nobles who participated in bullfighting and to prohibit an ecclesiastical burial for anyone killed in the ring.

The ban outraged Spaniards, so much so that the son of Emperor Charles I warned the pope that “bullfights are in the blood of the Spaniards to such a degree that if you attempt to deprive them of the fights, violence will surely ensue ” (Bernardino de Melgar y Abreu, “Fiestas de toros. Bosquejo histórico,” p. 142). Indeed, bullfights continued in Spain even during the ban, and by the papacy of Pope Clement VIII in 1596, bullfighting bans were relaxed, such that only particularly dangerous forms of bullfighting (ie, "mass bullfights" that involved several bulls) were banned.

By the late-17th century, bullfights took place in almost every major city in Spain, as well as in dozens of Spanish and Portuguese colonies around the world. For example, bullfighting took place in Peru by 1558 and in the Philippines by 1619.

Another major change took place during this era. Until the late-17th or early-18th centuries, bullfights were almost exclusively fought on horseback, as had been the tradition for a millennium. However, as matadors realized that their foot assistants were gaining more public acclaim than they were, they increasingly chose to fight on foot, too. Using capes to distract the bulls, they created the classical style of bullfighting known around the world today.

The bullfighting landscape continued to change drastically with the construction of permanent bullrings across Spain in the 18th century. With new public spaces dedicated to the spectacle and regular bullfights to entertain the public, bullfighting became more than a pastime for nobility: it became a real profession that matadors and other toreros were paid for, and it became an art and a sport that anyone could master, no matter their background. As a result, butchers, breeders, and other laborers who were already familiar with the behavior of bulls gradually emerged on the bullfighting scene.

Pedro Romero Killing the Halted Bull by Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1816)

By the 19th century, Spanish-style bullfights had spread to Bayonne, France; Lima, Peru; and even New Orleans, USA, to name just a few of the many cities that adopted the sport. New and particularly barbaric methods of bullfighting were also introduced at this time. For example, in some bullfights, the banderilleras (darts placed in the bull to weaken it before it is killed) were wrapped in small amounts of dynamite. As the dynamite exploded, the bull was sent flying around the arena. Other horrible and outdated practices were also used at this time: some bulls were beaten with sandbags before the fight to weaken them, some had vaseline rubbed in their eyes before the fight to partially blind them, and some had cotton stuffed in their ears so they would be less aware of the matadors movements.

Fortunately, all of these practices were completely banned by the late-19th and early-20th centuries, and all bullfighters in major arenas must now abide by rules and government decrees outlining how they must behave and how they must treat the bull. For example, bulls must be killed within 25 minutes after entering the arena, or else the bull will be pardoned. Still, many countries, such as Chile, Cuba, Uruguay, and Argentina banned bullfights during this era, due to understandable concerns about animal rights.

Still, the tradition remained strong in Spain, and the early-20th century saw the "Golden Age of Bullfighting," with matador Juan Belmonte earning the title of the greatest bullfighter of all time. Belmonte's deep understanding of bulls' predictable behaviors allowed him to work within inches of the bull, and his bold techniques such as standing erect and motionless were soon imitated by bullfighters everywhere. Meanwhile, Ernest Hemingway published his acclaimed first novel, The Sun Also Rises, in 1926, which in part follows a character's love affair with a young bullfighter during a trip to Pamplona, Spain. As a result of this wildly popular novel, millions of tourists have since travelled to Spain to experience this fiesta and Spanish bullfights in person.

Today, bullfights remain a very popular form of entertainment in Spain and across much of Latin America. If you attend the Running of the Bulls festival in Pamplona, Spain this July, you can witness several different types of bullfight events, including horseback bullfights, bloodless bull-leaping, and traditional Spanish bullfighting. If you're interested in experiencing this ancient sport, book your tickets here!